The story so far: “Delhi’s law and order is under the Central Government, but Delhi is now being known as the capital of crime,” lamented its ex-CM Arvind Kejriwal on December 14, 2024, in his letter to Union Home Minster Amit Shah. Accusing Mr. Shah of turning Delhi into a jungle raj, he said, “BJP is no longer able to handle the law and order situation in Delhi. The people of Delhi will have to unite and raise their voices.” Currently, Aam Aadmi Party’s (AAP) Atishi is the Delhi CM and Mr. Kejriwal is seeking his third term in the upcoming polls.

A continuing blame game has become a norm for the Delhi government and the Centre for the past ten years since power changed hands from the Congress to the BJP in the Centre and from the Congress to AAP in Delhi. The two governments have been bickering over various issues such as law and order, air and water pollution, and State revenues to name a few. While AAP has accused the Centre of curtailing the State government’s power rendering it unable to implement its policies, the BJP has accused AAP of sacrificing Delhi’s progress over petty politics.

Here’s a look at Delhi’s evolving power structure.

1947

In the Constituent Assembly in 1947, a discussion was held regarding the constitutional status of Centrally Administered Provinces such as Delhi, Ajmer, Coorg etc. After a seven-member committee led by Pattabhi Sitaramayya did a quick study (spanning less than three months), a report was submitting which recommended a separate self-government in Delhi. This would comprise a three-member Council of Ministers, a 50-member legislative Assembly and a Lieutenant Governor, making the nation’s capital a quasi-state of its own, former Lok Sabha secretary S.K. Sharma wrote in Frontline.

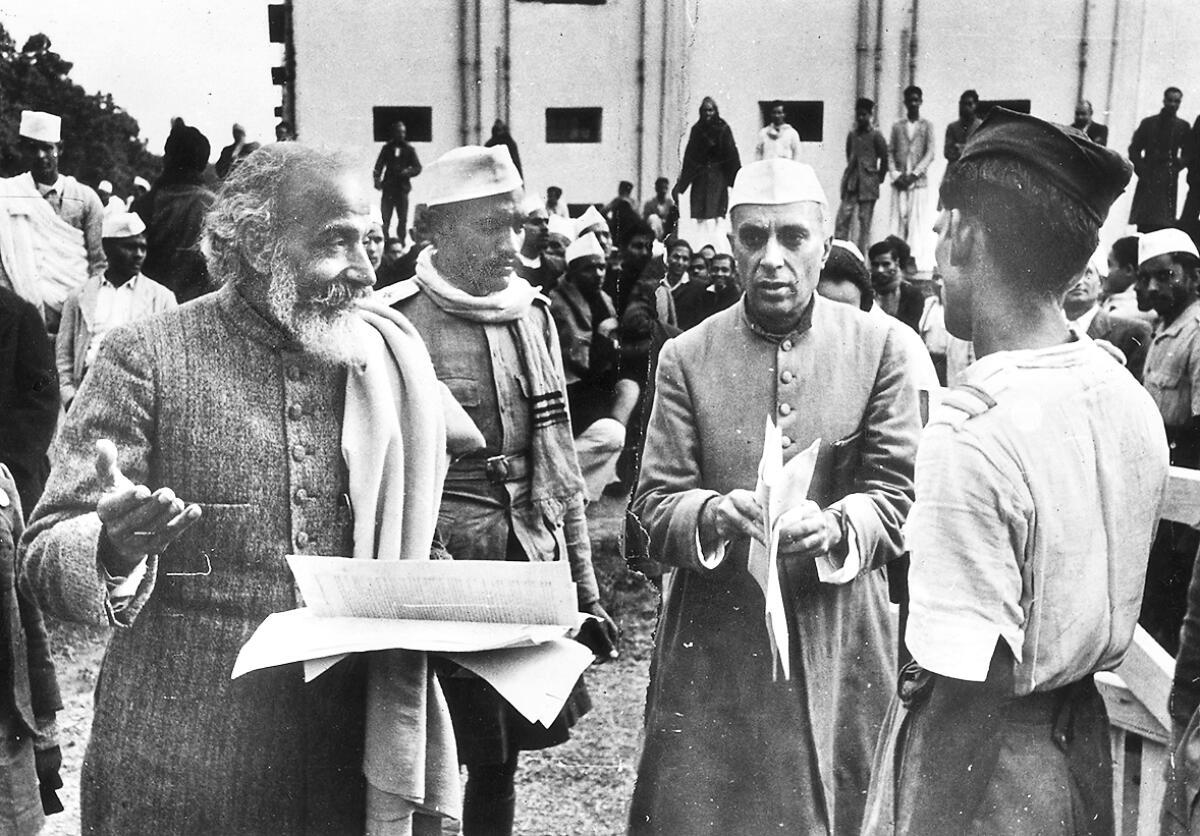

However, this recommendation was not accepted by most members of the Constituent Assembly. Led by then-Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, most Congress stalwarts like Sardar Vallabhai Patel and Dr. Rajendra Prasad felt that the Centre must have exclusive legislative powers and authority in Delhi. However, they faced strong pushback from several members of the above-mentioned committee, leading to a two-year delay in tabling the report.

File photo: On February 8, 1947, Indian statesman Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (1889 – 1964, facing camera) attends a meeting of the Constituent Assembly in the Council House Library, New Delhi, to decide on the constitution of the newly independent India.

Finally, a compromise was struck and in 1951, Delhi was made a part ‘C’ State (Former Chief Commissioner’s provinces). As per its classification, Delhi was given a 48-member Legislative Assembly, a Legislative Council and a Chief Minister. The Assembly was empowered to make laws related to all subjects listed in the State List of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution of India, except public order, police and land. In 1952, Congress chose 34-year-old Brahm Prakash as its first Chief Minister and he remained in the post till 1956.

1956-1991

In 1956, India was reorganised into States and Union Territories (UT) by the Parliament. Delhi was made a UT to be administered by an administrator appointed by the President. The Assembly and the Council were abolished, stripping Delhi of all legislative control.

However, the demand for a democratic set-up in the national capital kept growing and in 1966, the Delhi Administration Act was passed, setting up an Interim Delhi Metropolitan Council with an Executive Council. Defined as a ‘compromise between a representative body with full legislative and financial powers and administration by the President through his nominee,’ the Metropolitan council was headed by the Lieutenant Governor (L-G). Termed the ‘kingpin of Delhi Administration’, the L-G was empowered to summon and prorogue the Metropolitan Council within a time interval of six months.

Apart from the L-G, the Metropolitan Council comprised of a Presiding Officer, Leader of the House, Leader of the Opposition (LoP), Whips, Members, Secretary and Secretariat. The 61-member council had 56 elected members and five nominated members. The Council was headed by the Chairman who presided over the Council and had the final say (like a Speaker) on its proceedings. The Leader of the House, who was also the Chief Executive Councillor, advised the L-G along with his three-member Executive Council on all legislative matters related to the UT. While the Act had no provisions for an LoP, the Council traditionally recognised the leader of the largest party from the Opposition as an LoP, who was also nominated as the Chairman of the Committee on Assurances.

Between 1967 and 1990, the Congress remained the ruling party of the Council barring 1977-80, when the Janata Party-led government came to power in the Centre. Vijay Kumar Malhotra, Madan Lal Khurana and Kalka Dass,members of the Jan Sangh and later BJP, were the Council’s LoPs between 1967-77 and 1980-1991. This set up came to an end in 1991 when Delhi was granted special status.

1991-2013

Renaming the Union Territory as the ‘National Capital Territory of Delhi’ (NCT), the Parliament amended the Constitution to introduce two new Articles 239AA and 239AB. This first amendment provided for the setting up of a Legislative Assembly which had powers to make laws for NCT on matters in the State and Concurrent Lists, except for police, public order and land. Delhi’s executive structure was revamped giving it a Chief Minister annd Council of Ministers who would advise the L-G on the laws framed by the Assembly on the above-mentioned subjects. The President was tasked with appointing the Chief Minister and Council of ministers. He could also intervene in case of a dispute between the L-G and the Assembly.

The second amendment was made as a provision in case of failure of constitutional machinery. This allowed the President to suspend the operation of 239 AA (i.e. the elected Delhi Assembly and council of ministers) if he received a report from the L-G that administration of the NCT cannot be carried out.

Shortly, the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi Act, 1991 was enacted by Parliament to implement these Constitutional amendments. Defining the contours of the L-G’s powers, the Act clarified that he can only act on issues outside the Assembly’s powers and on those matters delegated to the President, as his representative. He was also allowed to exercise judicial or quasi-judicial functions and to exercise his discretion when required by any law.

“It is a triple chain of accountability. Bureaucrats are accountable to the minister, ministers to the legislature and the MLAs to the people,” explains Mr. Sanjoy Ghose, Senior advocate in the Supreme Court.

Sushma Swaraj being sworn in as the Delhi CM by then L-G Vijai Kapoor at Raj Bhavan on December 10, 1998.

Under this new restructuring,the Centre and Delhi’s State government often tussled over power. Between 1993 and 2024, BJP ruled Delhi for five years, the Congress for fifteen and now AAP for ten years. In 1993 to 1998, when the Congress was in power at the Centre, the BJP ruled Delhi with Mr. Khurana, Sahib Singh Verma and Sushma Swaraj splitting the five-year term among themselves. However, when power flipped hands at the Centre in 1998, Delhi chose to elect Congress thrice in 1998, 2003 and 2008. During her three terms as CM, Sheila Dikshit consolidated her power in Delhi, especially between 2004-2013, when the Congress-led coalition was in power at Centre.

2014 onwards

The arrival of Arvind Kejriwal as CM and Narendra Modi as the Prime Minister in 2014 took the power struggle to newer heights. With the Congress being wiped off the political scene in 2015 and 2020 State polls, BJP slowly began rebuilding its base in Delhi. In 2015, it won three seats and eight in 2020. In the Centre, BJP’s strength grew more rapidly, with the party winning 282 and 303 seats in the 543-seat Lok Sabha – giving it a single-party majority.

It was the Delhi High Court, in 2016, which held that Delhi continues to remain a Union Territory despite the existence of Article 239AA, making the L-G the executive head of NCT. Upset at the curtailment of its executive control, the AAP government challenged the judgment in the Supreme Court.

Two years later, the Supreme Court passed a judgement favouring the AAP government, unanimously ruling that the Chief Minister was the executive head of the NCT and that the L-G was to be consulted on all matters where Assembly has the power to make laws, but his concurrence was not required. It also stated that L-G cannot refer every matter where there is a conflict between LG and the Council of Ministers to the President.

Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal is welcomed by government officers and staff at the Delhi Secretariat in 2018

Post the 2019 Lok Sabha polls, which awarded the BJP a majority in the Lower House and a near-majority in the Upper House, Parliament amended the Government of National Capital Territory Act in 2021. It specifically reworked the SC’s judgement on Delhi government’s executive control. In the amended Act, the Assembly was barred from deliberating on matters related to daily administration of the NCT and prohibited from conducting inquiries into administrative decisions. The Act mandated the government to receive the L-G’s opinion on all executive decisions. It also mandated the President’s assent on Bills passed by the Assembly if it ‘incidentally’ covered matters outside its powers. The Kejriwal government has challenged the Act in the Supreme Court and the matter is still pending.

“Post these amendments to the National Capital Territory Act, they have completely neutered the elected government. Now, in fact, even if the assembly elections are held, you ultimately are electing a debating society because the elected government cannot even suspend a bureaucrat or have a say in their allocation,” says Mr. Ghose, when asked about what executive powers the Delhi CM holds now.

Commenting on AAP’s peculiar situation, he adds, “Aam Aadmi Party cannot politically admit this, because then people will question why even elect them.”

On May 11, 2023, a five-judge SC bench unanimously upheld the Delhi government’s power over administrative services in the NCT. It asserted that the democratically elected Delhi government cannot be deprived of its legislative and executive powers by the Centre.

Within a week, the Centre passed an ordinance negating the SC’s judgement. It designated the L-G as Delhi’s administrator who has the final say on the postings and transfer of all bureaucrats serving in Delhi. It also established the National Capital Civil Service Authority (NCCSA) which comprises of the Delhi CM and two Centre-appointed officials -Chief Secretary and Principal Home Secretary of Delhi. This authority will decide on transfer, posting and vigilance matters of all bureaucrats, via a majority of votes by the members.

In this Monday, Aug. 7, 2023 file image, former prime minister Manmohan Singh attends proceedings in the Rajya Sabha during the Monsoon session of Parliament, in New Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

–

Explaining the extent to which the ordinance strips the CM’s powers, Mr. Ghose says, “In Delhi, bureaucrats are absorbed from two cadres – Delhi, Andaman and Nicobar Islands Civil Service (DANICS) and Arunachal Pradesh-Goa-Mizoram and Union Territory (AGMUT) cadre. Now the central government may have the right to have a say in transfer postings as the bureaucrats are from different regions. But this ordinance goes a step further and says you as Chief Minister have no right to decide which officer shall be the Secretary for health or education.”

The ordinance was later followed with an amendment to the GNCT Act passed by Parliament in August that year. Both amendments and the ordinance has been challenged by the Delhi government.

“The Parliament may, by policy, change the Act, retrospectively, thereby not giving effect to a Supreme Court decision at all. Or by changing the date, it can take away the very basis of the decision. But if the Supreme Court gives out an interpretation, as it did in the services case, upholding it as a basic structure of the Constitution, then even Parliament cannot amend it,” says Mr. Ghose, when asked about the legality of such an amendment.

Commenting on the legal recourse left with the Delhi government, he says, “If Aam Aadmi Party government loses, the BJP will withdraw that case in the Supreme Court. However, if AAP wins, they will have to argue that Parliament could not have amended the law because you (SC) had interpreted it as part of basic structure. Unless the bureaucrats are brought under their control I don’t see how AAP can implement the promises made in their manifestos.”

Published – February 06, 2025 02:46 pm IST